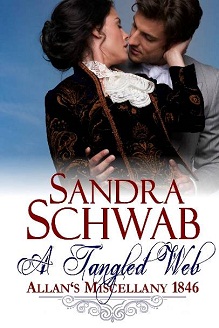

A Tangled Web - SANDRA SCHWAB | Historical Romance Author

Main menu:

- Welcome

-

Bookshelf

- Eagle's Honor

- Allan's Miscellany

- A Love for Every Season

- Stand-alone Novels

- About Sandra

- Research

- Author Services

- Contact

- Blog

A Tangled Web

Trivia

Throughout 1846 much ridicule was heaped on Matthew Cote Wyatt's planned statue of the Duke of Wellington on his horse Copenhagen.

Many Londoners considered it a monstrosity: the Daily News, for example, called it an "atrocious violation of all artistic principles" and an "artistic eyesore" (16 Sept 1846).

The artists and writers of the satirical magazine Punch took great delight in speculating whether the statue would be the cause for horrible nightmares or whether it would tear the world asunder when it fell off the triumphal arch on which it was to be placed.

Praise for A Tangled Web

"Once again [Schwab] weaves brilliantly researched historical details into a story that is not only irresistibly romantic, but also sparkles with wit. To top it off, she has come up with an enchanting couple that truly earns their happy ending."

~ Tina Dick, LoveLetter

Excerpt

London, September 1846

Fog rolled up from the river and wrapt the city in a white shroud. It muted the sounds of the busy metropolis and turned the people, the carts, and carriages out and about in the streets into ghostly apparitions.

An old-fashioned travelling coach made its way up Piccadilly towards Mayfair. Inside, a young woman sat ramrod straight and silent like a marble statue. She wore deep mourning and had her dark hair tied back into a severe knot, which emphasised the signs of tiredness etched into the skin around her eyes, making her look haggard and older than her twenty-nine years.

From time to time she would glance out of the window where shadows of the world flitted by as if it were the Lady of Shalott’s magic mirror.

Aunt Em had enjoyed Tennyson’s poems, so Sarah had been obliged to read them out aloud so often that she knew many of them by heart.

And there she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

Unlike the unfortunate Lady of Shalott, Sarah had never transgressed against the rules imposed upon her, had never looked out of the window of the enchanted tower, had never been led into temptation by a knight’s glittering armour.

No, Sarah had always been dutiful, had always submitted to her family’s wishes because, after all, she was just Sarah, the youngest daughter whom nature had not endowed with beauty. And so, by her family’s decision, her lot had been to be dutiful—for ten long years, when she had first cared for her ailing father and then later for her greataunt.

Now she returned to a home she had not seen in a decade, and in her carpet bag lay a letter from Aunt Em bearing the inscription To Miss Sarah Browne—for services rendered. Inside the envelope was a short note directing her to an adress here in London.

Not a word of affection, nor a word of thanks.

No, simply for services rendered as if she had been nothing more than a servant.

Sarah grimaced. Aunt Em had never been particularly affectionate, but she had always insisted on paying her debts—apparently even those owed to a dutiful greatniece.

When the coach finally arrived at her family’s elegant townhouse, there was nobody there to greet Sarah except for the maid, who directed her to a small room upstairs. Sarah was informed that after freshening up, she was to to to the study, where Mr. Browne awaited her.

And so, half an hour after her arrival, Sarah was sitting in her brother’s study, her hands placed in her lap, her eyes demurely lowered.

“You were late to arrive. I don’t see why you couldn’t take the train,” her brother said, his tone querulous. As the head of that respectable banking house of Philipps and Browne, Mr. Hobson Browne was used to his will being done and his word obeyed. Indeed, within his small corner of the financial world, his word was the law, not to be defied—certainly not by a younger sister, whose faded looks had placed her firmly on the shelf a long time ago. “It was very inconsiderate of you. Very inconsiderate indeed!”

“It is what Aunt Em would have wanted,” she replied evenly. “She rather hated the railway.”

“Yes, yes. That may as it be, but the old bird is dead now.” He rubbed his hands. “And at a most fortuitous time, too! Dear Mrs. Browne has despaired over finding a tutor for the twins. They are quite delicate children, you must know. Much too delicate to be sent to school—their mother wouldn’t hear of that! Yet to leave them in the sole charge of Nurse will not do either. ‘But why should we go to the expense of hiring a tutor?’ I said to Mrs. Browne. ‘Nothing would be more proper than for Sarah to teach the twins.’” He nodded. “It is the most proper and most economic solution—why, you wouldn’t have anything else to do!” Suddenly, his gaze sharpened. “Naturally, I expect you to fulfill this duty to greater satisfaction than you did your last one.”

Suprised, Sarah stared at him. “I have always been dutiful in the execution of—“

“Bah!” He glared at her. “Dutiful? When you did nothing to prevent Aunt Em give the bulk of her money—four thousand pounds!—to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals? Ha!” Agitatedly, he began to march up and down the room. “Who has ever heard of such a preposterous thing!”

“She was very fond of her small dog, who died five years ago,” Sarah offered.

“That”—Hobson whirled around and pointed a finger at her—“is no reason. Why-ever do you think we placed you under her roof? Got in faster than the other Brownes, too.—How they must have laughed at us when they heard of the will. Got eight-hundred pounds, didn’t they? And for what? For doing nothing! For shame! Aunt Em made us the laughing stock among our relatives. Giving us merely a thousand pounds! That old witch!” For a moment, he fumed in silence, then muttered angrily, “Never could stand me, the old hen. Never understood why.” He snorted, then seemed to remember Sarah’s presence, for he turned to glare at her once more. “I expect your work here will be more satisfactory.”

Sarah clenched her teeth, and reminded herself that, being twenty-nine years of age, unwed, with neither prospects nor fortune of her own, she was dependent on the charity of her relatives. So she kept her voice impassive as she answered, “I will strive to do my best, brother.”

“Yes, yes,” he said, his tone irritated. He waved his hand. “Now go. You will want to settle in your room, won’t you? Though I don’t expect it will take you much long.”

And thus, she was dismissed.